ABSTRACT

Objective: Efficient diagnostic pathways in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) are crucial for timely treatment initiation and improved outcomes. This study evaluated the impact of diagnostic delays and the role of minimally invasive techniques in biomarker assessment and survival in a real-world clinical cohort. Methods: A retrospective cohort study was conducted involving 205 patients with advanced NSCLC diagnosed between January 2020 and December 2023. Diagnostic procedures included EBUS/EUS-B, transthoracic biopsy, and surgical biopsy. The time-to-diagnostic procedure, time-to-therapy, and survival were analyzed using multivariate models. Results: The time interval to the first diagnostic procedure independently predicted mortality (HR=1.66; p=0.016). EBUS and EUS-B achieved significantly shorter diagnostic times (median 8 and 5 days, respectively) compared to transthoracic (20.5 days) and surgical (24.5 days) biopsies. These endoscopic techniques were also associated with shorter time intervals to systemic therapy initiation (p=0.011). Minimally invasive approaches provided sufficient tissue for complete morphological, immunohistochemical, and molecular profiling in most cases, with no significant differences in adequacy among procedures. Patients with actionable mutations had a 44% lower mortality risk (HR=0.56; p=0.013), while high PD-L1 expression was associated with a 56% reduction in mortality risk (HR=0.44; p=0.003). Conclusions: Minimally invasive techniques, particularly EBUS and EUS-B, shortened diagnostic delays, ensured adequate biomarker sampling, and enabled earlier initiation of systemic therapy. Since the time-to-diagnosis was independently associated with survival, these approaches may have indirectly contributed to improved outcomes. Our findings highlight the importance of streamlining diagnostic pathways and expanding access to endoscopic methods to optimize care in advanced NSCLC.

Keywords:

Non-small cell lung cancer; Diagnostic pathways; EBUS; EUS-B; Molecular profiling; Survival analysis.

INTRODUCTION Lung cancer (LC) remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide,(1) largely due to the high prevalence of late-stage diagnoses and consequent low survival rates.(2) NSCLC, which accounts for more than 85% of LC cases,(3) has become a central focus of clinical research and therapeutic innovation.(4,5) The development of targeted therapies for NSCLC has underscored the importance of precision-based diagnostic strategies, particularly in advanced stages.(5,6) In this context, molecular and immune profiling are essential to identify actionable biomarkers and guide treatment decisions,(7–9) yet their implementation continues to pose significant challenges in real-world clinical settings.

Comprehensive immunohistochemical and molecular profiling in advanced NSCLC often requires a myriad of invasive diagnostic approaches.(8,10,11) The choice of procedure is determined by a dynamic interplay between patient-specific factors—such as lesion location and overall health status—and healthcare resources, including equipment availability, staff expertise, and referral access.(12–14) These factors vary substantially across healthcare settings and are expected to evolve with ongoing technological innovation(14) and changing patterns of disease presentation.(6,15)

Although a growing body of research has explored the role of diagnostic pathways and biopsy techniques in the histological and molecular profiling of NSCLC,(8,10–12) evidence from large, long-term cohorts remains limited. This four-year cohort study aimed to address this gap by evaluating multiple diagnostic pathways for immunohistochemistry, programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), and actionable molecular targets. By analyzing outcomes related to the utility and timelines of various biopsy modalities, we sought to provide critical insights into how diagnostic strategies influence therapeutic decision-making and patient survival, thereby supporting the evidence-based selection of efficient diagnostic pathways in advanced NSCLC.

METHODS This retrospective cohort study included patients diagnosed with TNM stage IV NSCLC(16) between January 2020 and December 2023. Eligibility criteria required histopathological confirmation and attempted assessment of immunohistochemical and molecular profiling, as per clinical indication.(8) The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Francisco Gentil Portuguese Institute of Oncology of Coimbra (approval No. 23-2022, November 15, 2022), and informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal representatives.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics included age at diagnosis, sex, smoking status, and performance status according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale. The initial diagnostic procedure was defined based on the modality that enabled tissue acquisition for histopathological and biomarker evaluation. The procedures included videobronchoscopy, endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS), endoscopic transesophageal ultrasound using the echobronchoscope (EUS-B), computed tomography (CT) or ultrasound-guided transthoracic biopsies (TTB), surgical biopsies, and pleural procedures. The origin of the sample (primary lung tumor, lymph nodes, or metastatic lesion) was also documented.

For EBUS and EUS-B, samples were obtained using dedicated 22G needles, with at least three passes per lymph node station, in accordance with institutional protocol. Cytology smears and cell blocks were prepared, with the latter fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24–48 hours and embedded in paraffin (FFPE), serving as the primary material for histological, immunohistochemical, and molecular analyses. All other biopsy types were also processed as FFPE following the same protocol. Rapid On-Site Evaluation (ROSE) was not available for any sample type during the study period. All diagnoses were reviewed by a board-certified pathologist.

In addition to histological subtype classification, PD-L1 expression was evaluated by immunohistochemistry using the PD-L1 22C3 pharmDx assay on the Dako Autostainer Link 48 platform (Agilent Technologies, USA). Analyses were performed on FFPE tissue samples, and PD-L1 expression was reported as the percentage of tumor cells exhibiting positive membrane staining, in accordance with the reporting standards in place at the time of data collection.

Molecular profiling was performed using next-generation sequencing (NGS) on FFPE tumor samples with ≥10% tumor content. Nucleic acids were extracted with the MagMAX™ FFPE DNA/RNA Ultra Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and quantified using a Qubit® 3.0 fluorometer. Sequencing was carried out on the Genexus platform (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with the Oncomine™ Precision Assay GX, which enables the detection of mutations, copy number variations, and gene fusions across 50 cancer-related genes.

Key time intervals were systematically measured in days, and included: (1) the time from the initial clinical evaluation to the diagnostic procedure, serving as an indicator of procedural accessibility; (2) the time from the procedure to availability of histopathological and PD-L1 results; and (3) the time from histological diagnosis to the completion of the comprehensive molecular profiling, reflecting laboratory processing intervals.

The time to first-line therapy, treatment modalities, and survival outcomes—defined as the time interval to the last follow-up or death—were also analyzed in relation to diagnostic pathways and molecular findings.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 23 (IBM Corp., USA), with a significance threshold set at p<0.05. The Shapiro-Wilk test assessed the normality of continuous variables, and non-parametric methods were applied given the non-normal distribution. Descriptive statistics are presented as median and range (for age) and as median and interquartile range (IQR) for time intervals. The Kruskal-Wallis test compared time intervals, and the Fisher-Freeman-Halton exact test evaluated diagnostic yield for PD-L1 and molecular profiling. Overall survival was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier curves and the log-rank test. A multivariate Cox regression model identified independent predictors of survival and estimated hazard ratios (HR).

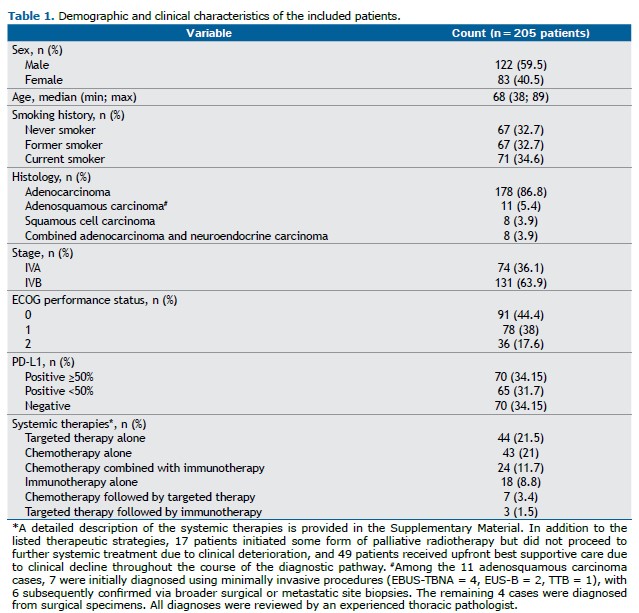

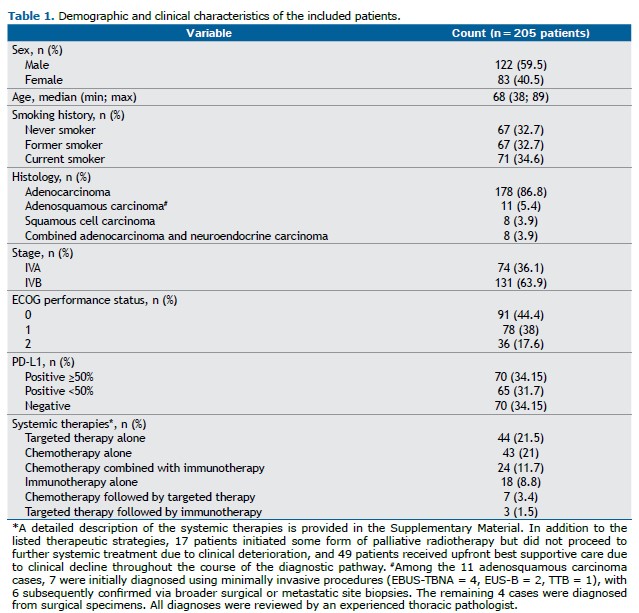

RESULTS The study cohort consisted of 205 patients, all diagnosed with stage IV NSCLC, of whom 74 (36.1%) were classified as stage IVA and 131 (63.9%) as stage IVB. Most patients were male (122, 59.5%), with females accounting for 83 cases (40.5%). The median age at diagnosis was 68 years (range: 38–89 years). All patients had an ECOG performance status ≤2. Detailed clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients are provided in Table 1.

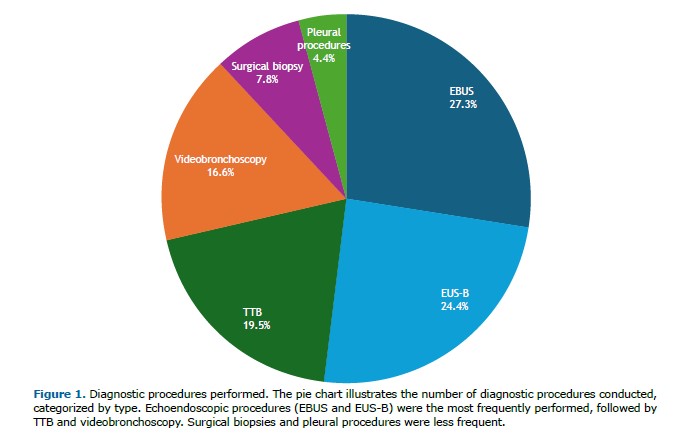

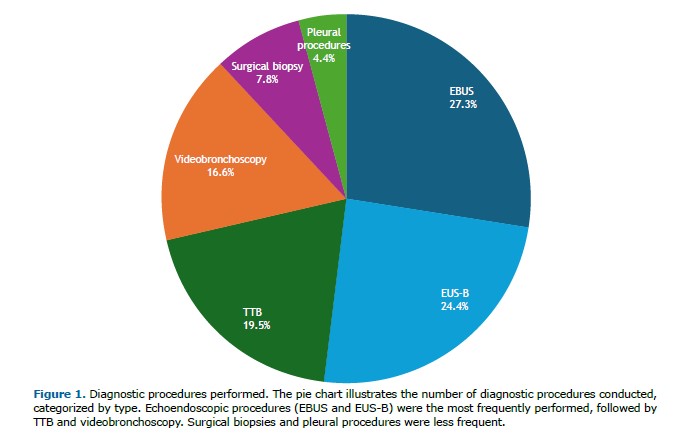

The most frequently adopted diagnostic procedures were EBUS, performed in 56 patients (27.3%), and EUS-B, in 50 patients (24.4%), totaling 106 cases (51.7%). Among the EBUS samples, 34 (60.7%) were obtained from mediastinal or hilar lymph nodes and 22 (39.3%) from primary tumors. For EUS-B, 38 samples (76.0%) were from mediastinal lymph nodes, 8 (16.0%) from primary tumors, and 4 (8.0%) from left adrenal metastases. Less frequently, TTB was conducted in 40 patients (19.5%), including 6 ultrasound-guided and 34 CT-guided procedures. Videobronchoscopy was carried out in 34 patients (16.6%), with 5 procedures assisted by radial EBUS. Surgical biopsies targeted extrathoracic lymph nodes (n=6), brain metastases (n=2), lung tumors (n=2), subcutaneous nodules (n=2), bone (n=2), pleura (n=1), and muscle (n=1), totaling 16 cases (7.8%). Pleural procedures comprised 5 thoracoscopies and 4 thoracenteses (4.4%). Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of diagnostic procedures.

Adenocarcinoma was the most common subtype of NSCLC, identified in 178 patients (86.8%), followed by adenosquamous carcinoma (5.4%), squamous cell carcinoma (3.9%), and combined adenocarcinoma with neuroendocrine carcinoma (3.9%). All procedures yielded sufficient material for histological and immunohistochemical characterization across the entire cohort. PD-L1 expression was assessed in all but two cases with insufficient material (1 EUS-B and 1 TTB). High expression (≥50%) was observed in 70 patients (34.2%), low expression (<50%) in 65 (31.6%), and negative expression in 70 (34.2%). The Fisher-Freeman-Halton exact test revealed no significant differences among procedures regarding PD-L1 testing success (p=0.757). Table 1 summarizes the histopathological and PD-L1 findings.

Molecular profiling was attempted in all patients, but was inconclusive in five cases (2.4%) due to insufficient material (2 EBUS, 1 EUS-B, 1TTB, and 1 videobronchoscopy). No statistically significant differences were found among the diagnostic procedures regarding molecular characterization (Fisher-Freeman-Halton exact test, p=0.968).

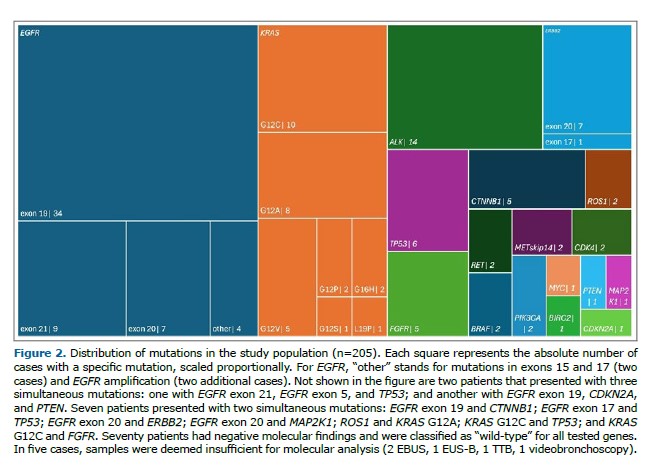

EGFR mutations were detected in 54 patients (26.3%), predominantly exon 19 deletions (34 cases). Other variants included exon 21 mutations (9 cases) and exon 20 insertions (7 cases). KRAS mutations were identified in 29 patients (14.1%), comprising G12C (10 cases), G12A (8 cases), G12V (5 cases), and rarer variants (G16H, G12P, G12S, and L19P), each observed in a single patient.

Additional driver mutations included ALK rearrangements (14 cases, 6.8%), ERBB2 (8 cases, 3.9%), TP53 (6 cases, 2.9%), as well as less frequent alterations in FGFR (5 cases, 2.4%), CTNNB1 (5 cases, 2.4%), ROS1 (2 cases, 1%), RET (2 cases, 1%), BRAF (2 cases, 1%), MET (2 cases, 1%), CDK4 (2 cases, 1%) and PIK3CA (2 cases, 1%). Detailed results are presented in Figure 2.

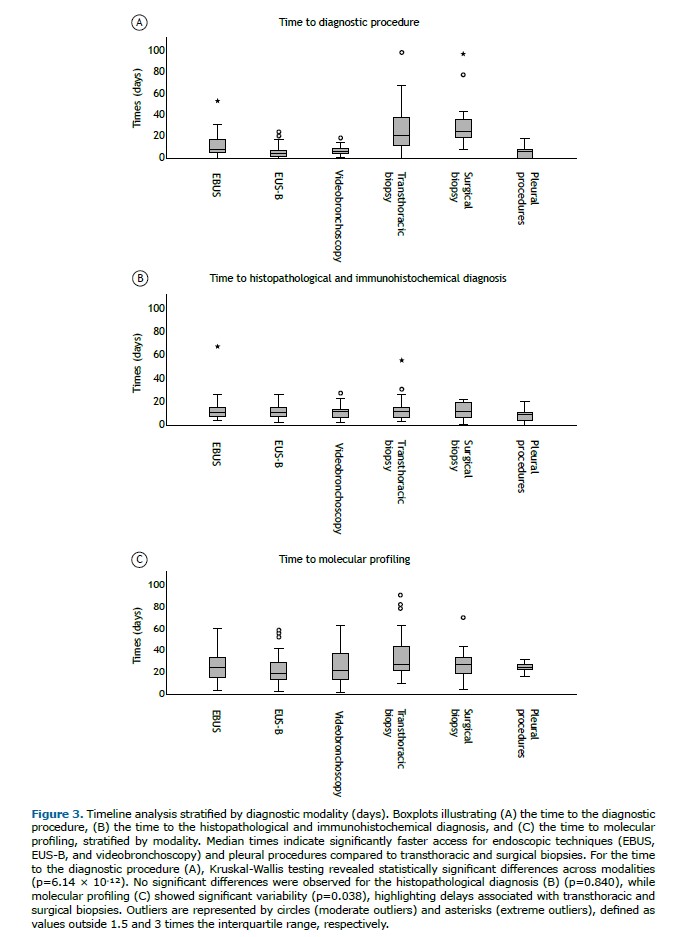

The overall median time from the initial evaluation to the first diagnostic procedure was 9 days (IQR: 4–18), although it varied significantly among modalities (Kruskal-Wallis test, p=6.14 × 10-¹²). Surgical biopsies (median: 24.5 days; IQR: 18–37.8) and TTB (median: 20.5 days; IQR: 12–38.3) were associated with the longest delays. In contrast, shorter intervals were observed for EUS-B (median: 5 days; IQR: 1.5–8), videobronchoscopy (median: 6.5 days; IQR: 4.3–9.5), pleural procedures (median: 7 days; IQR: 0–12.5), and EBUS (median: 8 days; IQR: 6–17.5 days).

The median time to obtain histopathological and immunohistochemical results was 11 days (IQR: 8–15.8), with no significant differences among diagnostic approaches (Kruskal-Wallis test, p=0.840).

The overall median time to obtain molecular results was 24 days (IQR: 16–35), with statistically significant differences across modalities (Kruskal-Wallis test, p=0.038). The longest intervals were seen with TTB (median: 31.5 days; IQR: 23–58) and surgical biopsies (median: 28 days; IQR: 14.5–50.5), followed by videobronchoscopy (median: 26.5 days; IQR: 14.3–43). Shorter durations were associated with EUS-B (median: 20 days; IQR: 14–29) and EBUS (median: 24 days; IQR: 15.3–35).

Figure 3 illustrates the differences in median times per diagnostic modality. Detailed time-interval data are provided in Supplementary Tables 1–3.

Most patients received systemic therapies tailored to their molecular and immunohistochemical profiles. Targeted therapy was administered in 21.5% of cases (n=44), while chemotherapy alone was given in 21% (n=43). Combination regimens included targeted therapy followed by immunotherapy (1.5%, n=3), chemotherapy followed by targeted therapy (3.4%, n=7), and chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy (11.7%, n=24). Immunotherapy alone was given to 8.8% of patients (n=18). A detailed overview is provided in Supplementary Table 4.

The time to the initiation of systemic therapy was analyzed by diagnostic procedure and treatment type. Significant differences were observed across the diagnostic modalities (Kruskal-Wallis test, p=0.011), with EUS-B (median: 59 days; IQR: 35.5–75.5), videobronchoscopy (median: 60 days; IQR: 48.5–72.5), and EBUS (median: 61 days; IQR: 49–87) associated with shorter intervals compared to surgical biopsies (median: 81 days; IQR: 50–121) and TTB (median: 82 days; IQR: 55.8–104.8). Targeted therapy showed the longest time to initiation (median: 72 days; IQR: 55–116), whereas chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy had the shortest (median: 61 days; IQR: 48–109). These differences, however, were not statistically significant (Kruskal-Wallis test, p=0.313). Supplementary Table 5 presents a detailed breakdown of these results.

A subset of patients received palliative or supportive interventions. Specifically, 17 (8.3%) initiated palliative radiotherapy but did not proceed to systemic therapy due to rapid clinical deterioration. In addition, 49 patients (23.9%) were allocated to upfront best supportive care, reflecting substantial clinical decline during the diagnostic and staging processes.

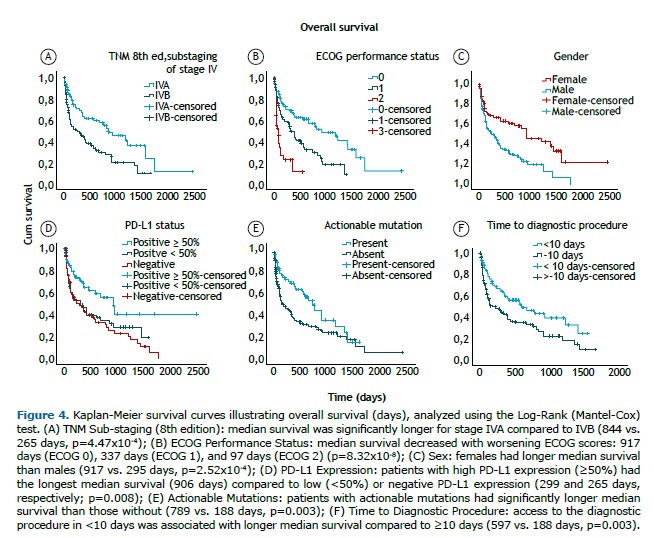

Multivariate Cox regression analysis identified several clinical and molecular factors as independent predictors of survival, with the ECOG performance status showing the strongest impact. Patients with ECOG 2 (HR=4.24; 95%CI: 2.38–7.52; p=1x10-7) and ECOG 1 (HR=2.29; 95%CI: 1.36–3.87; p=0.002) exhibited worse survival compared to those with ECOG 0. Sub-stage IVB (HR=1.78; 95%CI: 1.12–2.82; p=0.015) and male sex (HR=1.92; 95%CI: 1.36–3.87; p=0.004) were also significantly associated with higher mortality.

Regarding molecular markers, actionable mutations conferred a survival advantage (HR=0.56; 95%CI: 0.35–0.88; p=0.013). Similarly, patients with high PD-L1 expression (≥50%) exhibited better outcomes compared to those with negative PD-L1 expression (HR=0.44; 95%CI: 0.26–0.75; p=0.003).

Diagnostic efficiency, measured by the time to the first diagnostic procedure, was also an independent predictor of mortality, with each additional day of delay modestly increasing the risk (HR=1.15; 95%CI: 1.09–1.28; p=0.045). For practical interpretation, delays were dichotomized into <10 days and ≥10 days, based on the cohort’s median time to the first diagnostic procedure (9 days). Delays of 10 days or more were associated with a higher mortality risk (HR=1.66; 95%CI: 1.10–2.50; p=0.016).

Other variables—including age, smoking status, diagnostic modality, time to histological and molecular profiling results, and type of first-line therapy—were not statistically significant. Full results are detailed in Supplementary Table 6. Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed to further evaluate survival according to ECOG performance status, TNM sub-staging, sex, biomarkers, and the time to the diagnostic procedure (Figure 4).

DISCUSSION Optimizing diagnostic pathways in advanced NSCLC is paramount, as these decisions directly influence clinical timelines, therapeutic allocation, and ultimately, patient survival. This real-world study provides insights into both the challenges and opportunities associated with current diagnostic strategies.

Main findings The time to the first diagnostic procedure emerged as an independent predictor of mortality (HR = 1.66; p=0.016), highlighting the clinical importance of minimizing delays at this stage. This finding is particularly relevant in advanced NSCLC, where diagnostic delays can adversely affect survival, especially because therapeutic decisions depend on timely access to molecular biomarkers. Prolonged intervals between clinical evaluation, diagnostic procedures, and molecular profiling may postpone treatment initiation and reduce the likelihood of favorable outcomes.(17,18) Notably, endoscopic procedures such as EBUS and EUS-B accounted for most diagnostic approaches (51.7%, n=106) and achieved shorter diagnostic times compared to transthoracic or surgical biopsies. This likely reflects integrated pulmonology workflows that minimize logistic scheduling delays and reinforces the central role of endoscopic evaluation in efficient NSCLC diagnosis.(19)

Diagnostic workflows and the relevance of comprehensive biomarker testing Biomarker testing plays a crucial role in guiding treatment decisions in advanced NSCLC.(7–9) In this cohort, actionable mutations (HR=0.56; p=0.013) and high PD-L1 expression (HR=0.44; p=0.003) were associated with improved survival, supporting the clinical benefit of targeted therapies(18) and immune checkpoint inhibitors.(20)

Sample adequacy was high across all diagnostic modalities. Histological and immunohistochemical characterization was achieved in 100% of cases. PD-L1 assessment was possible in 98.9% of samples, while molecular profiling yielded conclusive results in 97.6%. Importantly, no statistically significant differences were observed between procedures for PD-L1 testing (p=0.757) or molecular profiling success (p=0.968), consistent with previous reports.(21,22) However, the time to obtain molecular results was longer for TTB (median: 31.5 days) and surgical biopsies (median: 28 days) than for EBUS (median: 24 days) and EUS-B (median: 20 days), likely reflecting additional logistical delays and the absence of reflex testing protocols that are more efficiently integrated within in-service pulmonology workflows.

Diagnostic efficiency and its impact on treatment allocation and survival Therapeutic approaches and their implications for survival were also explored in this cohort. Targeted therapy was the most frequently used modality (21.5%), reflecting the increasing reliance on precision medicine in advanced NSCLC. Conversely, 23.9% of patients received only best supportive care due to clinical deterioration, highlighting the challenges of managing a population often characterized by disease-related frailty.(24) The high proportion of patients unable to access systemic therapies due to clinical decline underscores the need for accelerated diagnostic pathways, as delays may preclude timely access to potentially life-prolonging treatments.(25,26)

These findings emphasize the clinical significance of diagnostic efficiency: patients with ECOG 2 had a fourfold increased risk of death compared to those with ECOG 0 (HR=4.24). Notably, endoscopic procedures were associated with shorter times to treatment initiation (p=0.011), further reinforcing their role in expediting therapy and potentially contributing to the survival benefit observed with earlier diagnostic interventions.

Furthermore, these survival disparities extend beyond ECOG performance status to include sex and TNM sub-stage, as demonstrated in our cohort and consistent with established prognostic factors in NSCLC.(16,25) The interplay of these factors highlights the critical importance of early and efficient diagnostic strategies, particularly in vulnerable patient populations.

Study limitations and future directions Despite its strengths, including a large, homogenous cohort and a real-world setting, the present study has limitations. Its single-center design may restrict the generalizability of findings, particularly in healthcare systems with different referral patterns, diagnostic resources, or access to specialized techniques. Nevertheless, the greater accessibility of interventional pulmonology procedures, such as EBUS and EUS-B, is likely relevant across diverse settings, as most NSCLC patients are initially managed in pulmonology clinics.(27) In contrast, procedures performed by other specialties, such as CT-guided TTB, require interdepartmental coordination, which may introduce delays, as observed in this study.(28)

The study’s retrospective design may also have introduced selection bias, potentially explaining the higher-than-expected proportion of adenosquamous carcinoma relative to squamous cell carcinoma, as patients referred for more extensive molecular characterization were likely overrepresented.

Although this study demonstrated that the time to the diagnostic procedure was an independent predictor of mortality, we could not confirm a direct survival advantage for patients undergoing endoscopic procedures as the frontline diagnostic modality, likely due to limited statistical power in stratified analyses. Nonetheless, their contribution to diagnostic timeliness suggests a potential indirect benefit, as part of the multidimensional factors influencing survival.(16,25)

Importantly, procedures such as EBUS and EUS-B, while valuable for mediastinal and central lesions, are less suitable for peripheral lesions, which typically require image-guided approaches such as TTB.(29) Emerging technologies—including ultrathin bronchoscopy, navigation bronchoscopy, cone beam CT, and robotic bronchoscopy—should be explored to expand the diagnostic reach and streamline workflows.(12,30–33) Another limitation is the variability in technological resources and specialized training across institutions. Although EBUS and EUS-B are increasingly accessible, disparities in equipment and expertise may constrain their broader adoption. Standardizing training pathways and ensuring equitable access to advanced diagnostic procedures are essential to overcoming these barriers to care. (34–36) Finally, reliance on minimally invasive procedures may be limited by small tissue samples.(21) In cases requiring multiple analyses, the material may not always sufficient, as observed in this study. One promising strategy to maximize available samples is to repurpose the supernatant phase, which contains free nucleic acids that can be leveraged for molecular profiling. Implementing this approach could enhance diagnostic capacity and reduce delays.(37)

Ultimately, this study highlights that, among the various factors influencing survival in advanced NSCLC, the time to the diagnostic procedure emerges as an independent and modifiable predictor of mortality. Our findings underscore the pivotal role of minimally invasive endoscopic techniques, particularly EBUS and EUS-B, which offer greater accessibility and efficiency in reducing diagnostic delays. The broad integration of these procedures into diagnostic pathways—supported by appropriate training and infrastructure—represents a tangible opportunity to enhance care and improve outcomes for patients with advanced NSCLC.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS All authors meet the ICMJE authorship criteria. LVR, RC, LTB, and VS made substantial contributions to the study’s conception and design. LVR, JO, and JD were responsible for data collection and acquisition from clinical files. LVR, JO, and LTB contributed significantly to the statistical analysis and interpretation of the data. LVR, RC, LTB, and VS contributed to drafting the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content, approved the final version, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring its accuracy and integrity.

REFERENCES 1. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–63. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834.

2. Woodard GA, Jones KD, Jablons DM. Lung Cancer Staging and Prognosis. Cancer Treat Res. 2016;170:47–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40389-2_3.

3. Lu T, Yang X, Huang Y, Zhao M, Li M, Ma K, et al. Trends in the incidence, treatment, and survival of patients with lung cancer in the last four decades. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:943–53. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S187317.

4. Araghi M, Mannani R, Heidarnejad Maleki A, Hamidi A, Rostami S, Safa SH, et al. Recent advances in non-small cell lung cancer targeted therapy; an update review. Cancer Cell Int. 2023;23(1):162. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-023-02990-y.

5. Li MSC, Mok KKS, Mok TSK. Developments in targeted therapy & immunotherapy—how non-small cell lung cancer management will change in the next decade: a narrative review. Ann Transl Med. 2023;11(10):358. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-22-4444.

6. Herbst RS, Morgensztern D, Boshoff C. The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature. 2018;553(7689):446–54. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25183.

7. Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aisner DL, Akerley W, Bauman JR, Bharat A, et al. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 3.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20(5):497–530. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2022.0025.

8. Planchard D, Popat S, Kerr K, Novello S, Smit EF, Faivre-Finn C, et al. Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(Suppl 4):iv192–iv237. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy275.

9. Hendriks LE, Kerr KM, Menis J, Mok TS, Nestle U, Passaro A, et al. Oncogene-addicted metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023;34(4):339–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2022.12.009.

10. Osmani L, Askin F, Gabrielson E, Li QK. Current WHO guidelines and the critical role of immunohistochemical markers in the subclassification of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC): Moving from targeted therapy to immunotherapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2018;52(Pt 1):103–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.11.019.

11. Rivera MP, Mehta AC, Wahidi MM. Establishing the Diagnosis of Lung Cancer: Diagnosis and Management of Lung Cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(5):e142S–e165S. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.1435S1.

12. Nooreldeen R, Bach H. Current and Future Development in Lung Cancer Diagnosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(16):8661. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22168661.

13. Alexander M, Kim SY, Cheng H. Update 2020: Management of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Lung. 2020;198(6):897–907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-020-00407-5.

14. Shafiq M, Lee H, Yarmus L, Feller-Kopman D. Recent Advances in Interventional Pulmonology. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16(7):786–96. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201901-044CME.

15. Ciofiac CM, Mămuleanu M, Florescu LM, Gheonea IA. CT Imaging Patterns in Major Histological Types of Lung Cancer. Life. 2024;14(4):462. https://doi.org/10.3390/life14040462.

16. Chansky K, Detterbeck FC, Nicholson AG, Rusch VW, Vallières E, Groome P, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: External Validation of the Revision of the TNM Stage Groupings in the Eighth Edition of the TNM Classification of Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(7):1109–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2017.04.011.

17. Restrepo JC, Martínez Guevara D, Pareja López A, Montenegro Palacios JF, Liscano Y. Identification and Application of Emerging Biomarkers in Treatment of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Systematic Review. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16(13):2338. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16132338.

18. Simarro J, Pérez-Simó G, Mancheño N, Ansotegui E, Muñoz-Núñez CF, Gómez-Codina J, et al. Impact of Molecular Testing Using Next-Generation Sequencing in the Clinical Management of Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in a Public Healthcare Hospital. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(6):1705. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15061705.

19. Sampsonas F, Kakoullis L, Lykouras D, Karkoulias K, Spiropoulos K. EBUS: Faster, cheaper and most effective in lung cancer staging. Int J Clin Pract. 2018;72(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.13053.

20. Kilaru S, Panda SS, Moharana L, Mohapatra D, Mohapatra SSG, Panda A, et al. PD-L1 expression and its significance in advanced NSCLC: real-world experience from a tertiary care center. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2024;36(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43046-024-00207-5.

21. Labarca G, Folch E, Jantz M, Mehta HJ, Majid A, Fernandez-Bussy S. Adequacy of Samples Obtained by Endobronchial Ultrasound with Transbronchial Needle Aspiration for Molecular Analysis in Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(10):1205–16. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201801-045OC.

22. Chaddha U, Hogarth DK, Murgu S. The role of endobronchial ultrasound transbronchial needle aspiration for programmed death ligand 1 testing and next generation sequencing in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7(15):351. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2019.03.35.

23. Rolfo C, Denninghoff V. Globalization of precision medicine programs in lung cancer: a health system challenge. Lancet Reg Health– Eur. 2023;36:100819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2023.100819.

24. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Collaborative Group. Chemotherapy and supportive care versus supportive care alone for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2010(5):CD007309. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007309.pub2.

25. Owusuaa C, Dijkland SA, Nieboer D, van der Heide A, van der Rijt CCD. Predictors of Mortality in Patients with Advanced Cancer—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(2):328. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14020328.

26. Kitazawa H, Takeda Y, Naka G, Sugiyama H. Decision-making factors for best supportive care alone and prognostic factors after best supportive care in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):19872. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-56431-w.

27. Griffiths S, Power L, Breen D. Pulmonary endoscopy – central to an interventional pulmonology program. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2024;18(11):843–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/17476348.2024.2413561.

28. Byrne SC, Barrett B, Bhatia R. The impact of diagnostic imaging wait times on the prognosis of lung cancer. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2015;66(1):53–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carj.2014.01.003.

29. Magnini A, Fissi A, Cinci L, Calistri L, Landini N, Nardi C. Diagnostic accuracy of imaging-guided biopsy of peripheral pulmonary lesions: a systematic review. Acta Radiol. 2024;65(10):1222–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/02841851241265707.

30. Matsumoto Y, Kho SS, Furuse H. Improving diagnostic strategies in bronchoscopy for peripheral pulmonary lesions. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2024;18(8):581–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/17476348.2024.2387089.

31. Verhoeven RLJ, Kops SEP, Wijma IN, Ter Woerds DKM, van der Heijden EHFM. Cone-beam CT in lung biopsy: a clinical practice review on lessons learned and future perspectives. Ann Transl Med. 2023;11(10):361. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-22-2845.

32. Kops SEP, Heus P, Korevaar DA, Damen JAA, Idema DL, Verhoeven RLJ, et al. Diagnostic yield and safety of navigation bronchoscopy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lung Cancer. 2023;180:107196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2023.107196.

33. Diddams MJ, Lee HJ. Robotic Bronchoscopy: Review of Three Systems. Life (Basel). 2023;13(2):354. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13020354.

34. Sehgal IS, Dhooria S, Aggarwal AN, Agarwal R. Training and proficiency in endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: A systematic review. Respirology. 2017;22(8):1547–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.13121.

35. Aslam W, Lee HJ, Lamb CR. Standardizing education in interventional pulmonology in the midst of technological change. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12(6):3331–40. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2020.03.104.

36. Steinfort DP, Evison M, Witt A, Tsaknis G, Kheir F, Manners D, et al. Proposed quality indicators and recommended standard reporting items in performance of EBUS bronchoscopy: An official World Association for Bronchology and Interventional Pulmonology Expert Panel consensus statement. Respirology. 2023;28(8):722–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.14549.

37. Gan Q, Roy-Chowdhuri S. Small but powerful: the promising role of small specimens for biomarker testing. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2020;9(5):450–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasc.2020.05.001.

English PDF

English PDF

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to cite this article

How to cite this article

Submit a comment

Submit a comment

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket