ABSTRACT

Objective: Despite advances in diagnosis and treatment, approximately 50% of individuals affected by tuberculosis develop post-tuberculosis lung disease (PTLD), leading to functional limitations and reduced quality of life (QoL). Pulmonary rehabilitation programs have demonstrated benefits in patients with PTLD; however, access remains limited, and telerehabilitation may offer a cost-effective solution. This study sought to compare physical capacity and QoL in patients with PTLD following an eight-week telerehabilitation program. Methods: This was a randomized controlled trial including 30 participants with confirmed PTLD. They were recruited and randomly assigned to an intervention group that received weekly telerehabilitation or a control group that received standard care. The interventions included aerobic training, breathing exercises, strength training, and stretching exercises. Physical capacity and QoL were assessed before and after the interventions by means of isokinetic dynamometry, the six-minute walk test, the five-repetition sit-to-stand test, spirometry, handgrip strength, the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), and the Saint George's Respiratory Questionnaire. Results: After eight weeks, the intervention group showed significant improvements in all physical capacity parameters and QoL. Quadriceps strength correlated significantly with the physical functioning and mental health domains of the SF-36. Conclusions: Our findings suggest that telerehabilitation is an effective approach for enhancing physical function and QoL in patients with PTLD.

Keywords:

Tuberculosis, pulmonary; Physical Therapy Modalities; Telehealth; Physical Fitness; Exercise.

INTRODUCTION Pulmonary tuberculosis remains the leading cause of death from infectious diseases, with approximately 8.2 million cases diagnosed in 2023. This is the highest recorded number of cases since 1997. However, a 5.4% reduction in mortality was observed in comparison with 2022, likely due to an increase in the number of individuals receiving treatment (76-78%), despite global funding remaining below the target set by the WHO.(1)

Despite advances in diagnostic methods and therapeutic medications, it is estimated that approximately 50% of affected individuals develop long-term sequelae, leading to some degree of functional limitation or impaired quality of life (QoL), which characterizes post-tuberculosis lung disease (PTLD).(2-4)

PTLD requires a multidisciplinary approach, including permanent preventive measures to avoid reinfection and participation in pulmonary rehabilitation programs in certain cases. This approach has demonstrated significant benefits in functional recovery and improved QoL, with positive effects on physical capacity, fatigue levels, social participation, and overall health status.(5-7)

The number of rehabilitation centers worldwide is insufficient to meet the demands of patients with various functional limitations caused by different diseases. One potential strategy to expand access to these services is the implementation of telerehabilitation programs, enabling patients to complete at least part of the rehabilitation protocol at home. This approach offers advantages such as enhanced mobility and reduced treatment costs.(8-16)

There have been no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on telerehabilitation in patients with PTLD. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to evaluate the effects of a telerehabilitation program on the physical capacity and QoL of patients with PTLD.

METHODS Study design, setting, and participants This was a single-center RCT conducted at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro—located in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil—in collaboration with the Istituti Clinici Scientifici Maugeri—a referral center in the city of Tradate, Italy—which supported the study design and statistical analysis, following the guidelines established in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials statement.(17)

Participants were recruited from among those followed at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro Tuberculosis Outpatient Clinic and underwent an initial screening that included a clinical interview (with dyspnea being assessed by the modified Medical Research Council scale), imaging tests (chest X-rays or CT scans), complete blood count, and biochemical profile assessment. Selected individuals with confirmed PTLD underwent QoL and physical capacity assessment.

Eligible patients had a Mini-Mental State Examination score > 24 (range, 0-30) and confirmed PTLD, as evidenced by residual lesions detected through clinical examination (clinical history, symptom assessment, and physical examination), imaging tests (chest X-rays or CT scans), functional assessment (spirometry, SpO2 measurement, or the six-minute walk test [6MWT]), and/or subjective evaluation (QoL questionnaire or frequent symptoms score).(3,18)

Individuals with comorbidities that could interfere with the assessments or those unavailable for telemonitoring via videoconference were excluded. Participants were excluded if adverse events hindered their participation in weekly videoconferences or their ability to perform the prescribed exercises as outlined in the study protocol.

Control variables and outcome measures The instruments, methods, and variables used in the present study included the following: a) general physical examination, including body weight and height, measured with a mechanical scale with a stadiometer (110 CH; Welmy, Santa Bárbara D’Oeste, Brazil); systemic blood pressure, measured with an aneroid sphygmomanometer (Premium®; Missouri Mikatos, Embu, Brazil); SpO2 and HR, measured with a portable pulse oximeter (9500; Nonin Medical, Inc., Plymouth, MN, USA); and RR, measured with a digital stopwatch; b) standard spirometry, performed with a single-user spirometer (Koko Sx®, nSpire Health Inc., Longmont, CO, USA) and analyzed in accordance with Brazilian national guidelines for pulmonary function tests(19,20); c) body composition assessment via tetrapolar multifrequency bioelectrical impedance analysis, performed with a body composition analyzer (InBody 230®; InBody Co. Ltd., Seoul, Korea); d) QoL assessment with the Saint George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ)(21) and the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) (22); e) calf circumference measurement, muscle mass being considered reduced if < 33 cm in women and < 34 cm in men(23); f) the 6MWT, performed in accordance with the recommendations of the American Thoracic Society, the expected six-minute walk distance (6MWD) for the Brazilian population being taken into consideration for analysis(24,25); g) The five-repetition sit-to-stand test (5STS), leg strength being considered reduced if test duration > 14 s(26,27); h) handgrip strength, measured with a Jamar hydraulic hand dynamometer (Sammons Preston, Bolingbrook, IL, USA), with results being expressed in kg/f and being compared with reference values for the Brazilian population(28); and i) isokinetic dynamometry of the leg muscles, a Biodex® isokinetic dynamometer (Lumex Inc., Ronkonkoma, NY, USA) being used in order to evaluate muscle strength and fatigue of the dominant leg on the basis of peak torque of the quadriceps and hamstring muscles, 75°/s (5 repetitions) and 240°/s (15 repetitions) being performed with 2 min resting time.(29)

Randomization and masking Consecutive participants completing antituberculosis treatment and meeting the inclusion criteria were randomly assigned to either the intervention or control group using a block randomization method, with a block size of four. An independent statistician who was not involved in participant recruitment, treatment, or assessment prepared a computer-generated randomization sequence. Treatment assignments were concealed in opaque, sealed envelopes, which were opened sequentially after participants provided written informed consent and completed the baseline assessments.

Intervention and reevaluation The intervention and control groups received general guidance on pulmonary tuberculosis symptoms and prevention during the initial face-to-face consultation and weekly videoconferences.

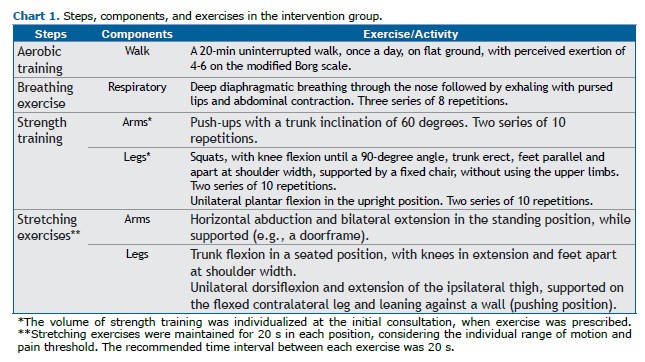

The intervention group received physiotherapy care via telemonitoring (telerehabilitation) once a week. This included an initial face-to-face consultation, in which a personalized exercise program was prescribed and demonstrated. The participants were instructed to perform the exercises for 45 min per day, five days per week (> 200 min/week) for eight weeks. During the videoconferences, adherence to the exercise program was evaluated, questions were addressed, and modifications (e.g., adjustments in repetitions, sets, or duration) were made as needed.(30)

Information on the program was provided via an illustrated booklet, with a tracking page for exercise completion. The exercises were divided into four parts: aerobic training, breathing exercises, strength training, and stretching. Exercise volume was prescribed on the basis of individual functional capacity, with a 20-s rest between sets (Chart 1).(3,5,30)

After eight weeks, reevaluation of the intervention and control groups was performed by blinded examiners, who used the same research instruments to measure QoL and physical capacity in both groups. After data collection and analysis, all of the individuals in the control group were provided with full guidance to perform the same intervention protocol as that performed by the intervention group.

Sample size and data analysis A sample size calculation indicated that 40 participants would be ideal on the basis of a pilot study assessing the 6MWD. With the use of the Student’s t-test (α = 5%; power = 80%), a minimum of 30 participants were found to be required for statistical significance.

Statistical analysis was performed with SigmaStat, version 3.1 (Grafiti LLC, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Data distribution was assessed with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Associations between variables were analyzed with Spearman’s or Pearson’s correlation coefficient, as appropriate. Comparisons were performed with Fisher’s exact test, ANOVA, the Student’s t-test, or their nonparametric equivalents. Differences and correlations were considered significant at p < 0.05.

The local research ethics committee approved the study protocol (CAAE 10481219.9.0000.5257), and the study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04844502). All participants provided written informed consent. The study protocol was published elsewhere,(31) detailing the design, methodology, and planned analyses of the present RCT.

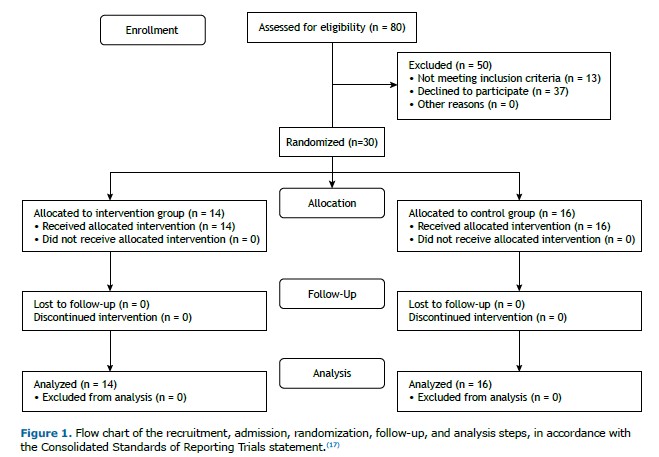

RESULTS Eighty individuals were recruited. After the eligibility criteria were applied, 30 participants (11 females and 19 males) were randomized (Figure 1). Notably, all enrolled participants fully adhered to the study, and no adverse events occurred during the eight-week protocol.

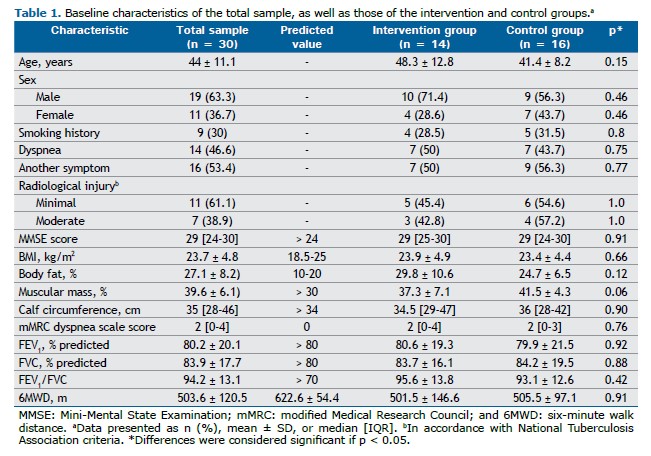

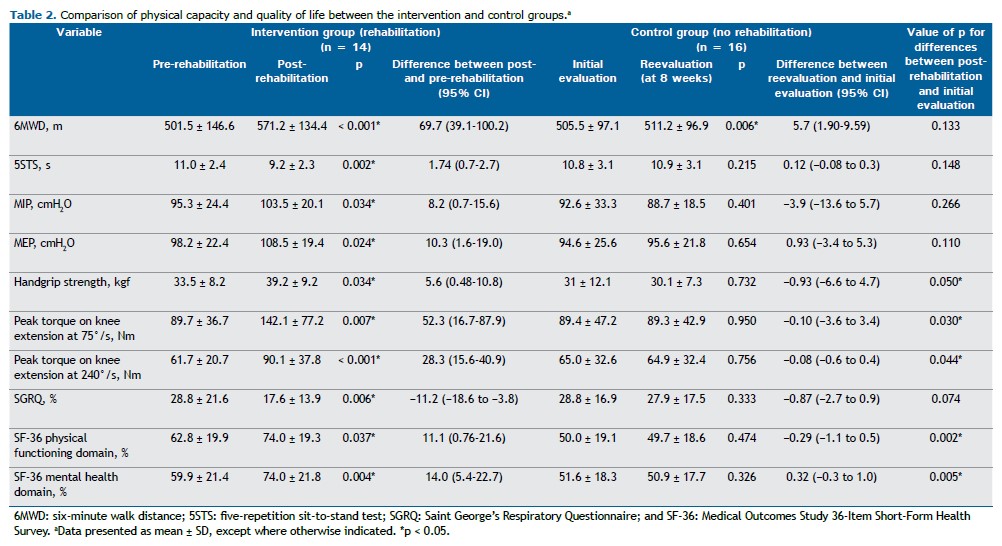

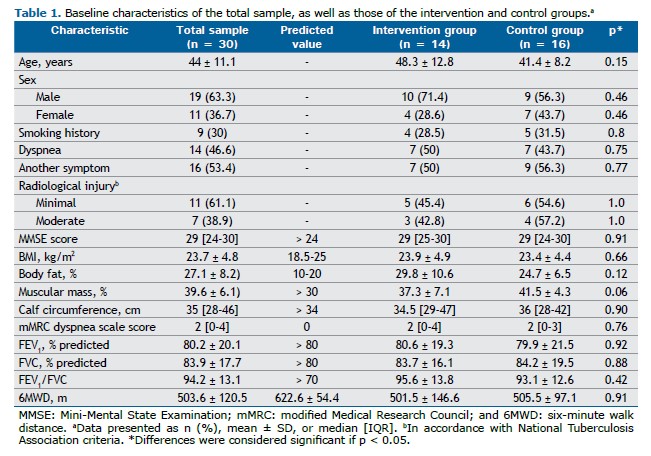

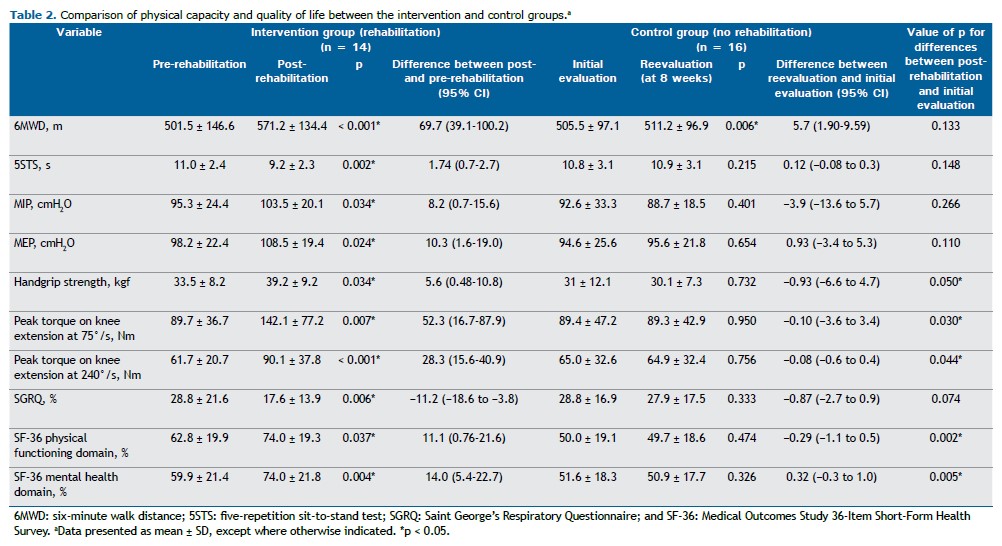

Participant characteristics obtained through medical history taking, medical record review, physical examination, and spirometry are presented in Table 1. Comparisons between the control and intervention groups showed no significant differences at the initial assessment. The results for physical capacity and QoL, obtained from initial and follow-up assessments of the intervention (rehabilitation) and control (nonrehabilitation) groups, were compared, with the differences and confidence intervals presented in Table 2. Comparisons between the post-rehabilitation group and the initial control group were made, and no clinically significant differences were observed.

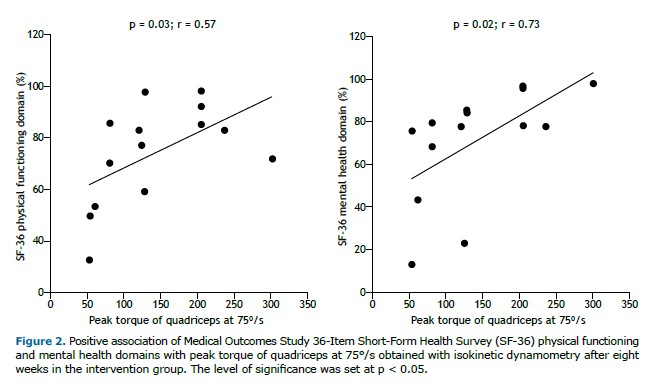

After eight weeks of intervention, significant improvements were observed in all physical capacity parameters within the intervention group, including comparisons with predicted values for the 6MWD: predicted value for the total sample, 622.6 ± 54.4 m vs. pre-intervention value, 503.6 ± 120.5 m, corresponding to 80.9 ± 19.0%; predicted value for the intervention group, 601.5 ± 46.9 m vs. post-rehabilitation value, 571.2 ± 134.4 m, corresponding to 95.0 ± 21.4%. Additionally, overall QoL as assessed by the SGRQ improved, along with notable gains in the physical functioning and mental health domains of the SF-36. Quadriceps muscle strength was positively associated with SF-36 physical functioning and mental health domains (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION This was the first RCT on telerehabilitation in patients with PTLD. Our results show that, in a cohort of patients with PTLD and functional limitations, an eight-week pulmonary telerehabilitation program led to significant improvements in peripheral muscle strength and endurance, as well as in the physical functioning and mental health domains of the SF-36. When we evaluated pre- and post-intervention differences, the telerehabilitation group alone demonstrated improvements across all the study variables. However, the differences were not fully reflected in the between-group analysis, likely because of the small sample size.

In one study,(32) 85 patients with PTLD (26 females and 59 males) were evaluated, and a slight reduction in physical capacity, as measured by the 6MWT, was found, along with significant radiographic abnormalities and pulmonary function impairment in 70% of the cases. Patients with more significant radiographic sequelae showed impaired performance on the 6MWT when compared with those with smaller residual lesions (85.07 ± 12.27 vs. 90.96 ± 6.18% of the predicted value).(32) This result reinforces the need for rehabilitation programs for this population. Similarly, in our study, an improvement corresponding to 14.1% of the predicted value was observed after the intervention.

In another study,(33) positive outcomes from a six-week rehabilitation therapy program were demonstrated. The study included 29 patients, of whom 52% were female. The study participants completed a supervised group-based rehabilitation protocol twice per week combined with daily home-based exercise instructions. The supervised rehabilitation program consisted of educational sessions on health topics (including the effects of respiratory diseases, self-care, exercise, and diet), 30 min of walking, and anaerobic exercises for the arms and legs. After six weeks, the group showed a significant reduction in symptoms, improvements in functional tests (including the incremental shuttle walk test and the 5STS), and enhanced QoL (as assessed by the Clinical COPD Questionnaire and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9), which persisted for an additional six weeks after the intervention.(33) Our study did not employ the same instruments for assessing QoL; however, despite the fact that we used a telerehabilitation approach, we observed similar results, with a significant improvement in 5STS performance when comparing the pre- and post-intervention groups.

In a study involving 26 patients,(34) of whom 54% were female, a supervised rehabilitation protocol was implemented twice per week. After six weeks, the authors observed a nonsignificant improvement in functional performance on the 6MWT (an increase of 34 m in the 6MWD; p = 0.3), which contrasts with our findings (an increase of 69.7 m in the 6MWD; p < 0.001). However, they reported a significant improvement in QoL, as measured by the SGRQ (a reduction of 17% in the scores; p = 0.002),(34) consistent with our results (i.e., a reduction of 11% in the scores; p = 0.006).

In yet another study,(35) the benefits of a home-based rehabilitation program for this population were assessed in an RCT involving a six-week intervention and 67 participants. The rehabilitation program consisted of low-impact exercises for the arms and legs (wall push-ups, repeated sit-to-stand movements, and calf raises), and participants were encouraged to “walk faster” each day during the walking component of the program. Specific pulmonary exercises included pursed-lip breathing, diaphragmatic breathing, postural correction, and cough facilitation exercises. Exercise tolerance was assessed by the 6MWT, demonstrating a significant improvement in the intervention group in comparison with the control group (p = 0.007; 95% CI, 15.37-92.7),(35) which contrasts with our findings (p = 0.133). This might be due to differences in sample size or in patient engagement and commitment to carrying out the home-based protocol.(35)

Post-intervention pulmonary function was not specifically assessed in the present study. However, one study conducted a comparative analysis of pre- and post-intervention groups and reported no significant differences in FEV1 (p = 0.1; 95% CI, −0.07 to 0.51) or FVC (p = 0.2; 95% CI, −0.9 to 0.51). These findings contrast with those of a multicenter study by Silva et al.,(36) who reported significant improvements (p < 0.01) in pulmonary function outcomes following in-person rehabilitation programs lasting at least five weeks (20 nonconsecutive days) in a sample of 85 patients with PTLD. These discrepancies are likely due to differences in sample size and intervention protocols.(35,36)

There have been no studies examining the use of isokinetic dynamometry as the primary tool for objectively assessing changes in physical capacity in patients with PTLD.(29) However, one study demonstrated the effectiveness of this assessment method in more than 3,000 participants with COPD. (37) In our study, the sensitivity and applicability of isokinetic dynamometry were evident, highlighting muscle strength and fatigue (peak torque on knee extension) as key outcomes in the initial assessment and their improvement when we compared pre- and post-intervention measurements, as well as their association with perceived QoL.

The limitations of the present study include the absence of a disease-specific QoL questionnaire for patients with PTLD and the impossibility of replicating the research protocol in centers lacking isokinetic dynamometry equipment, which may have restricted the number of participants. The low sample size did not allow us to stratify results by COPD status, given that approximately one third of our patients had a smoking history. Furthermore, because we did not perform pre- and post-rehabilitation spirometry, we were unable to confirm the functional improvement reported elsewhere.(38)

The implementation of rehabilitation programs with innovative, effective, and low-cost strategies for PTLD treatment is currently a topic of discussion in clinical practice.(39) We sought to contribute through a simple, safe, low-cost, and effective telerehabilitation protocol. This approach seeks to facilitate the implementation of public health policies in regions with a high prevalence of PTLD and a limited number of rehabilitation centers. The only basic requirement to implement similar projects is the availability of a smartphone and an internet connection.

The present study demonstrated that an eight-week telemonitored rehabilitation program using videoconferencing had a positive effect on physical capacity and overall QoL in patients with PTLD. These findings reinforce current recommendations for continued care following the pharmacological treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis and highlights telemonitoring as a valuable tool in the functional recovery process.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study is part of the scientific activities of the Global Tuberculosis Network, hosted by the World Association for Infectious Diseases and Immunological Disorders. The authors wish to thank Francesca Ferrari for her editorial support in developing the manuscript.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS DFMT: design and planning of the study, as well as interpretation of findings; writing of all preliminary drafts and the final version; and approval of the final version. FSG: design and planning of the study; revision of all preliminary drafts and the final version. NASM: interpretation of findings and writing of all preliminary drafts. APC: design and planning of the study; and revision the final version. GBM: design and planning of the study; and revision of all preliminary drafts and the final version. FCQM: design and planning of the study, as well as interpretation of findings; and revision and approval of the final version.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST None declared.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT This study received partial financial support from the Istituti Clinici Scientifici Maugeri via the Italian National Ministry of Health Fondo Ricerca Corrente.

FCQM was supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Brazil (Grant # 308556/2025-9).

REFERENCES 1. World Health Organization (WHO) [homepage on the Internet]. Geneva: WHO; c2024 [updated 2024 Oct 29; cited 2025 Jun 1]. Global Tuberculosis Report 2024. Available from:. https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on-tuberculosis-and-lung-health/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2024

2. Silva DR, Santos AP, Visca D, Bombarda S, Dalcomo MMP, Galvão T, et al. Brazilian thoracic association recommendations for the management of post-tuberculosis lung disease. J Bras Pneumol. 2023; 49(6):e20230269. https://doi.org/10.36416/1806-3756/e20230269

3. Migliori GB, Marx FM, Ambrosino N, Zampogna E, Schaaf HS, Zalm MM, et al. Clinical standards for the assessment, management and rehabilitation of post-TB lung disease. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2021; 25(10):797-813. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.21.0425

4. Allwood BW, Nightingale R, Agbota G, Auld S, Bisson GP, Byrne A, et al. Perspectives from the 2nd International Post-Tuberculosis Symposium: mobilising advocacy and research for improved outcomes. IJTLD Open. 2024;1(3):111-123. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtldopen.23.0619

5. Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, ZuWallack R, Nici L, Rochester C, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(8):13-64. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201309-1634ST

6. Silva DR, Pontali E, Kherabi Y, D’Ambrosio L, Centis R, Migliori GB. Post-TB Lung Disease: Where are we to Respond to This Priority? Arch Bronconeumol. 2025;61(5):262-263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arbres.2025.03.001

7. Nightingale R, Carlin F, Meghji J, McMullen K, Evans D, Zalm MM, et al. Post-TB health and wellbeing. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2023;27:248-283. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.22.0514

8. Fioratti I, Fernandes LG, Reis FJ, Saragiotto BT. Strategies for a safe and assertive telerehabilitation practice. Braz J Phys Ther. 2021;24(2):113-116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjpt.2020.07.009

9. Babu AS, Arena R, Ozemek C, Lavie CJ. COVID-10: a time for alternative models in cardiac rehabilitation to take centre stage. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36:792-794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2020.04.023

10. Cottrell MA, Russell TG. Telehealth for musculoskeletal physiotherapy. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2020;48:102193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msksp.2020.102193

11. Maddison R, Rawstorn JC, Stewart RAH, Benatar J, Whittaker R, Rolleston A, et al. Effects and costs of a real-time cardiac telerehabilitation: randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. Heart. 2019;105:122-129. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2018-313189

12. Souza Y, Silva KM, Condesso D, Figueira B, Noronha Filho AJ, Rufino R, et al. Use of a home-based manual as part of a pulmonary rehabilitation program. Respir Care. 2018;63(12):1485-1491. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.05656

13. Hwang R, Morris NR, Mandrusiak A, Bruning J, Peters R, Korczyk D, et al. Cost-utility analysis of home-based telerehabilitation compared with centre-based rehabilitation in patients with heart failure. Heart Lung Circ. 2019;28(12):1795-1803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2018.11.010

14. Mani S, Sharma S, Omar B, Paungmali A, Joseph L. Validity and reliability of internet-based physiotherapy assessment for musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23(3):379-391. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X16642369

15. Chan C, Yamabayashi C, Syed N, Kirkham A, Camp PG. Exercise telemonitoring and telerehabilitation compared with traditional cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiother Can. 2016;68(3):242-51. https://doi.org/10.3138/ptc.2015-33

16. Nolan CM, Kaliaraju D, Jones SE, Patel S, Barker R, Walsh JA, et al. Home versus outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD: a propensity-matched cohort study. Thorax. 2019;74:996-998. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212765

17. Cuschieri S. The CONSORT statement. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13(Suppl 1):S27-S30. https://doi.org/10.4103/sja.SJA_559_18

18. Arevalo-Rodriguez I, Smailagic N, Roqué-Figuls M, Ciapponi A, Sanchez-Perez E, Giannakou A, et al. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the early detection of dementia in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;27;7(7):CD010783. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010783.pub3

19. Pereira CA, Sato T, Rodrigues SC. New reference values for forced spirometry in white adults in Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2017;33(4)397-406. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132007000400008

20. Neder JA, Andreoni S, Castelo-Filho A, Nery LE. Reference values for lung function test. I. Static volumes. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1999.32(6):703-717. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-879X1999000600006

21. Sousa TC, Jardim JR, Jones P. Validation of the Saint George’s Respiratory Questionnaire in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2000;26(3):119-128. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-35862000000300004

22. Campolina AG, Bortoluzzo AB, Ferraz MB, Ciconelli RM. Brazilian-Portuguese version of the SF-36. A reliable and valid quality of life outcome measure. Rev Bras Reumatol. 1999;39(3):143-150.

23. Aliberti MJR, Szlejf C, Covinsky KE, Lee SJ, Jacob-Filho W, Suemoto CK. Prognostic value of a rapid sarcopenia measure in acutely ill older adults. Clin Nutr. 2020,39:2114-2120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2019.08.026

24. ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: guidelines for the 6-minute walk test. Am J Crit Care. 2002;166: 111-7. https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102

25. Britto RR, Probst VS, Andrade AFD, Samora GAR, Hernandes NA, Marinho PEM, et al. Reference equations for the six-minute walk distance based on a Brazilian multicenter study. Braz J Phys Ther. 2013;17(6):556-563. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-35552012005000122

26. Jones SE, Kon SSC, Canavan JL, Patel MS, Clark AL, Nolan CM, et al. The five-repetition sit-to-stand test as a functional outcome measure in COPD. Thorax. 2013;68:1015-1020. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203576

27. Bohannon RW. Reference values for the five-repetition sit-to-stand test: A descriptive meta-analysis of data from elders. Percept Mot Skills. 2006;103(1):215-22. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.103.1.215-222

28. Santos NR, Lopes AJ, Menezes SLS, Lima TRL, Ferreira AS, Guimarães FS. Handgrip strength in healthy young and older Brazilian adults: development of a linear prediction model using simple anthropometric variables. Kinesiology. 2017;49(2):208-216. https://doi.org/10.26582/k.49.2.5

29. Dvir Z, Müller S. Multiple-joint isokinetic dynamometry: a critical review. J Strength Cond Res. 2020;34(2):587-601. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002982

30. World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour: at a glance. Geneva: WHO, 2020.

31. Torres DFM, Guimarães FS, Cardoso AP, Mello FCQ. Telerehabilitation in post-tuberculosis lung disease: a protocol for a randomized controlled clinical trial. Int J Clin Trials. 2024;11(4):238-288. https://doi.org/10.18203/2349-3259.ijct20243331

32. Bansal N, Arunachala S, Ullah MK, Kulkarni S, Ravindran S, Shankara Setty RV, et al. Unveiling Silent Consequences: Impact of Pulmonary Tuberculosis on Lung Health and Functional Wellbeing after Treatment. J Clin Med. 2024;13:4115. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13144115

33. Jones R, Kirenga BJ, Katagira W, Singh SJ, Pooler J, Okwera A, et al. A pre-post intervention study of pulmonary rehabilitation for adults with post-tuberculosis lung disease in Uganda. Int J COPD, 2017;12:3533-39. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S146659

34. Hussain A, Khurana AK, Goyal A, Kothari SY, Soman RK, Tej S, et al. Effect of pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with post-tuberculosis sequelae with functional limitation. Indian J Tuberc. 2024;71(2):123-129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijtb.2023.04.012

35. Grass D, Manie S, Amosun SL. Effectiveness of a home-based pulmonary rehabilitation programme in pulmonary function and health related quality of life for patients with pulmonary tuberculosis: a pilot study. Afr Health Sci. 2014;14(4):866-72. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v14i4.14

36. Silva DR, Mello FCQ, Galvão TS, Dalcomo M, Dos Santos APC, Torres DFM, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with post-tuberculosis lung disease: a prospective multicentre study. Arch. Bronconemol. Published online February 22, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arbres.2025.02.007

37. Stoffels AA, Meys R, Hees HWH, Franssen FME, Borst B, Hul AJ, et al. Isokinetic testing of quadriceps function in COPD: feasibility, responsiveness, and minimal important differences in patients undergoing pulmonary rehabilitation. Braz J Phys Ther. 2022;26:100451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjpt.2022.100451

38. Zawedde J, Abelman R, Musisi E, Nyabigambo A, Sanyu I, Kaswabuli S, et al. Lung function and health-related quality of life among adult patients following pulmonary TB treatment. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2024;28(9):419-426. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.24.0029

39. Pontali E, Silva DR, Marx FM, Caminero JA, Centis R, D’Ambrosio L, et al. Breathing back better! A state of the art on the benefits of functional evalua-tion and rehabilitation on post-tuberculosis and post-COVID lungs. Arch Bronconeumol. 2022;58(11):754-763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arbres.2022.05.010

English PDF

English PDF

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to cite this article

How to cite this article

Submit a comment

Submit a comment

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket